Words by Ian Ramsey

Maine. February. It’s nearly an hour past sunset and I’m snowshoeing by headlamp deep in the backcountry of Baxter State Park, Maine’s crown jewel of wilderness. As I sink into the powder, crossing a set of moose tracks, I feel the weight of the sled that I’m pulling behind me. Just ahead, Jed is slogging as well, trying to keep his sled from tipping over in the drifted-over unused trail full of blowdowns. Where we expected this trail to be packed down, no one has been on this trail all winter, and we’ve been traveling all day, far slower than expected. Even further ahead, our friends Jason and Joe are looking for the Russell Pond bunkhouse, our destination. Within an hour, we’ll slog to a frozen lake ringed by boreal forest, and we’ll stagger into the cabin along its shore, light a fire in the woodstove and settle in.

Jason. Joe. Jed. Three old friends. Joe-an old friend of mine from college-married Jed’s sister, which is how I met Jed and Joe, who are cousins whose moms are identical twins, making them about as close as brothers. Since meeting them, I ended up moving around the corner from Jason, and Jed ended up buying the house of my partner Heidi’s parents. I like to say that northern New England is one small town, and our myriad intersections are a great example of it. Nevertheless, I rarely see these guys with all of our lives taken up with jobs, kids, adult responsibilities. Aside from getting out to skate ski with Joe two years ago, or waving to Jason as I bike past his yard, I haven’t actually seen these guys in several years.

For nearly twenty years, these guys have been making annual winter trips in Baxter. They come in the summer, or in the fall as well, with their families or by themselves. But these winter trips are different. Dude trips. Soul trips. Trips to check in with each other, to be quiet for long hours on the trail, to sit around the woodstove and catch up without the distraction of technology or responsibilities. The earth is quiet at this time of the year. Not to say that there aren’t plenty of fart jokes and howls at the moon, but these trips are a chance to share adventure, masculine energy, hard work, wildness, gear experimentation, and physical endurance. In time in our lives when we’re probably as busy as we’ve ever been, it is important to share a different kind of slower, more thoughtful time, and to reconnect to something deeper, especially this year, when we have been barricading ourselves against the realities of covid for nearly a year.

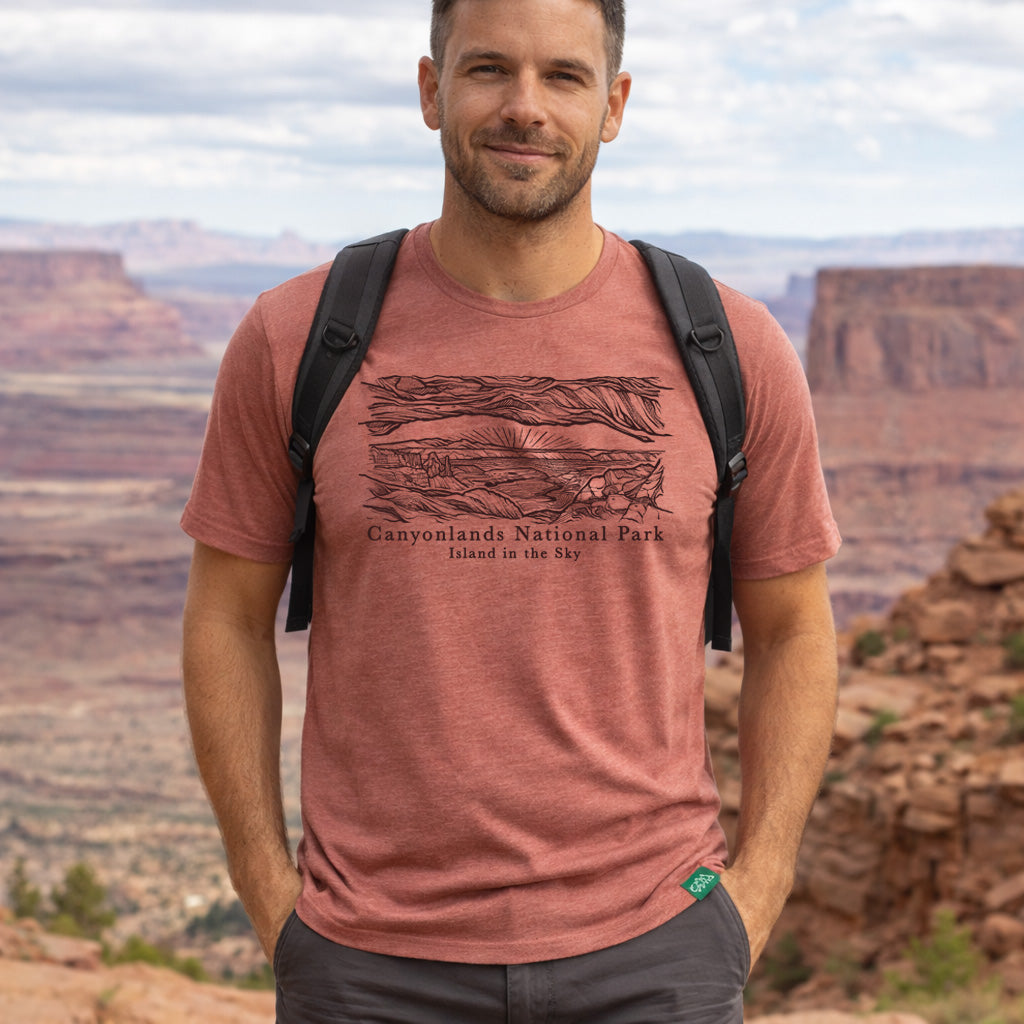

Standing on the lake with our sleds full of gear

It’s been a decade since I last journeyed with these guys-the last time I was just a couple of months out from finishing chemo for testicular cancer, and the trip, where we skied across the length of the park, was an affirmation that my health and spirit weren’t as shaken as I had feared. In the years since, I’ve been divorced and found a new partner, Jed and his wife have had a little girl, and Jason and Joe’s kids are almost all teens. There have been new careers, new homes, and myriad other changes, and yet here we are again, dozens of miles from anyone deep in the backcountry, talking about everything from families to music while our damp, stinky socks steam over the woodstove.

Baxter and other shared public lands offer us a kind of Sabbath from the ever-increasing rush of the world, a chance to center and connect, to breathe and reset. Time in these places is a kind of pattern interrupt from our daily lives that allows us to reassess and reintegrate, refocus and slow down. Instead of screens, we look at pine trees. Instead of tapping on keyboards, we tap on janky camping stoves to get them started. We worry about keeping our fingers warm, not our online calendar. With our senses prehistorically alert to the scent of spruce bows and wind, dry socks and dark chocolate are sources of far greater happiness than almost anything in daily life. After enduring much of the Maine winter of short, cold days on top of Covid sheltering, to share an adventure with others feels downright ecstatic, even if blisters and sore knees are also part of the bargain.

Skinning with sleds full of gear

As I sip whiskey and listen to these three men talk about family members I don’t know, I’m struck by several things. First off, the brotherhood that these three men share is beautiful. Deepened by raising kids, burying relatives, raising kids, and sharing holidays, their quiet, casual bond has an unspoken resonance and commitment. As someone who has never had brothers, or kids, or much of a close extended family, I’m in awe of the strength that they share from their bonds and the way they embody their fatherhood, their brotherhood, their familyhood, their tribe. Secondly, as they talk about different trails in the park that they’ve explored or want to explore, I’m struck by how well they know this place. While I’ve visited Baxter and the surrounding area throughout my entire lifetime, my adventures have more often taken me further afield, often to distant, exotic places. But for all my stories of the Andean glaciers, Alaskan bears and Vietnamese bike mishaps, I haven’t gotten to know this prominent corner of my homeplace as well as these guys. Jed, as a trail builder, in particular, often works in this area, and has an impressive intimacy with this landscape and the local communities. But for all three, this is clearly their place, their refuge. I’m reminded of the Spanish term querencia, a term used by bullfighters to describe the place in the bullring where the bull feels strong and safe, but that in the more broad, human sense, means the place where one’s strength of character is drawn from, where one renews and re-centers oneself, where, as Barry Lopez writes, “we know exactly who we are. The place from which we speak our deepest beliefs.” For all that I know as a lifelong Mainer, it’s clear to me that I have much to learn from guys about this place, about my own life. Finally, I’m filled with gratitude that they’ve included me in this adventure, in their lives. Where it might be easy for them to keep the trip to themselves, they’ve included me, and I feel incredibly grateful.

But for now, in this tiny backcountry cabin, we’ll catch up about our lives, our families, the things we’re thinking about and feeling. We’ll sip on peppermint schnapps and tea and eat freeze-dried meals of dubious quality that taste amazing in the backcountry. Tomorrow we’ll ski the trails around this cabin, and marvel at the myriad animal tracks and the quality of the light in the sky. We’ll think about how this is ancient Abenaki land and wonder how we might best honor the legacy and rights of the Penobscot people who were here first. We’ll belly laugh and boil drinking water and drink waay too much coffee. We’ll sit in silence, talk for hours, and repair my sled that broke while we were crossing a steep, frozen stream. And the day after, we’ll rise at 5AM to snowshoe and ski the 20+ miles out of here, through hours of falling snow, not seeing anyone for most of the day. We’ll arrive at the trailhead at sunset, just in time to drive home, already thinking about the next time that we can get back up here.

|

Ian Ramsey is a writer, educator, wilderness traveler, and musician. For twenty years he has been on the faculty of North Yarmouth Academy, where he teaches environmental writing. brain science, physiology, music, mindfulness, and leads student trips. Ian holds an MFA in creative writing from the Rainier Writing Workshop and has published poems and essays in a variety of national publications. A licensed Maine Guide and aspirant BCU Five Star Sea Kayak Leader, he has coached at the Midcoast Sea Kayak Rendezvous, and has paddled throughout North America, the Bahamas, Wales, the Sea of Okhotsk, Vietnam, and Central America. |